I've noticed a trend among the rationalist movement of favoring long and convoluted articles referencing other long and convoluted articles--the more inaccessible to the general public, the better.

I don't want to contend that there's anything inherently wrong with such articles, I contend precisely the opposite: there's nothing inherently wrong with short and direct articles.

One example of significant simplicity is Einstein's famous E=mc2 paper (Does the inertia of a body depend upon its energy-content?), which is merely three pages long.

Can anyone contend that Einstein's paper is either not significant or not straightforward?

It is also generally understood among writers that it's difficult to explain complex concepts in a simple way. And programmers do favor simpler code, and often transform complex code into simpler versions that achieve the same functionality in a process called code refactoring. Guess what... refactoring takes substantial effort.

The art of compressing complex ideas into succinct phrases is valued by the general population, and proof of that are quotes and memes.

“One should use common words to say uncommon things” ― Arthur Schopenhauer

There is power in simplicity.

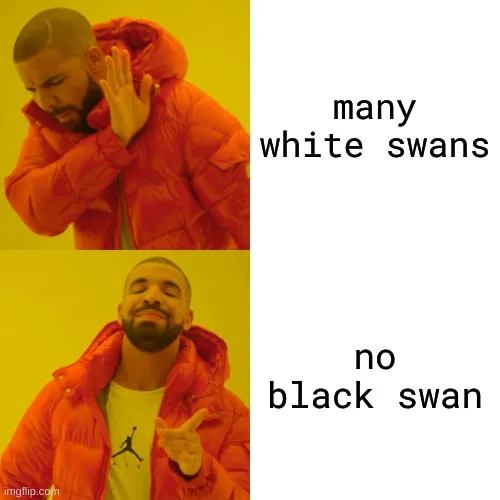

One example of simple ideas with extreme potential is Karl Popper's notion of falsifiability: don't try to prove your beliefs, try to disprove them. That simple principle solves important problems in epistemology, such as the problem of induction and the problem of demarcation. And you don't need to understand all the philosophy behind this notion, only that many white swans don't prove the proposition that all swans are white, but a single black swan does disprove it. So it's more profitable to look for black swans.

And we can use simple concepts to defend the power of simplicity.

We can use falsifiability to explain that many simple ideas being unconsequential doesn't prove the claim that all simple ideas are inconsequential, but a single consequential idea that is simple does disprove it.

Therefore I've proved that simple notions can be important.

Jump in the discussion.

No email address required.

Notes -

Two competing Pre-Reqs on this: Watch This TikTok video and read This Borges Short Story. Both are short, the TikTok is a minute and the short story is 4 pages, so plenty concise.

Now compare the two. The notch on the book is so precise a metaphor that while the whole book is communicated by that notch, it is a code so complex that it would require absurdly accurate skill in measurement and mathematics to interpret. Even within the thought experiment, most people would assume that it would require some kind of complex microscope and computerized calculator to achieve. But let's go a step further. Let's imagine a superhuman who can see the notch on the metal rod and instantly measure the ratio visually, calculate the ratio, and interpret that into the written work. So that merely by showing such a man astick, I've sent him Funes the Memorius as surely as emailing you the pdf. But that requires both an immense amount of baseline skill, and a huge degree of education and recall. In understanding the code, and in the mathematics necessary to interpret it.

On the reverse of the coin is Funes, who Borges' narrator describes as

Part of what makes Funes the way he is, is that before his superhero origin story he is an uneducated farmhand. He is raw intellect undiluted. He does not have the mental processes to encode things in a quick and useful way.

The reason so many Rationalist/Adjacent writers, and Mottizens are in this group, write at such length is because they and their audience lack metaphors and symbols for the concepts they are discussing. Two well read and well trained philosophers or theologians can argue almost entirely in metaphors; Baridan's Ass or Schrodinger's Cat or You Can Never Step in the Same River Twice or the Melian Dialogue or Pascal's Gamble or a Faustian Bargain or Funes the Memorius.* A few words and a whole mass of concepts and ideas and metaphors floods the brain. To a well-read Westerner, just by saying Funes the Memorius (or in some cases, "hey remember that Borges short story you read in undergrad with the guy who remembered everything?") I have achieved the same thing the stick did in the thought experiment. But both require common education and skill. The rationalist writer is often stepping out of his own education, and his audience is a generally intelligent but not particularly specialized group of readers. Everything has be explained from first principles, like Funes' useless numbering system.

*This is why I'm in favor of a classics based education. I gives you common ground to discuss. And the metaphors you get from the Bible and the Iliad are critical to interpreting Faust and Dante, which are critical to interpreting all the literature that comes after that.

But we use those and more all the time. Pascal’s gambit and Schrodinger’s cat are almost too cliché for this venue. We have Pascal’s mugging, Moloch, a dane you can’t get rid of, a nazi who knocks, a cathedral, russell’s teapot, theseus’s ship, falsification, steelmanning, nash equilibrium, hypoagency, p hacking, oneboxing, backpacker harvesting, utility monsters, specks of dust, beliefs paying rent, pareto optimums, spherical cows, and, last but not least, the motte.

People’s complaints about this place are usually the opposite: that we use too much jargon, that we are being deliberately obscure. Or they will say the specifically rationalist concepts are not original. Which has a degree of truth, but if the point is to write more concisely, we still need to use the original term for the concept, and nothing will have been gained by switching names.

More options

Context Copy link

More options

Context Copy link