I've noticed a trend among the rationalist movement of favoring long and convoluted articles referencing other long and convoluted articles--the more inaccessible to the general public, the better.

I don't want to contend that there's anything inherently wrong with such articles, I contend precisely the opposite: there's nothing inherently wrong with short and direct articles.

One example of significant simplicity is Einstein's famous E=mc2 paper (Does the inertia of a body depend upon its energy-content?), which is merely three pages long.

Can anyone contend that Einstein's paper is either not significant or not straightforward?

It is also generally understood among writers that it's difficult to explain complex concepts in a simple way. And programmers do favor simpler code, and often transform complex code into simpler versions that achieve the same functionality in a process called code refactoring. Guess what... refactoring takes substantial effort.

The art of compressing complex ideas into succinct phrases is valued by the general population, and proof of that are quotes and memes.

“One should use common words to say uncommon things” ― Arthur Schopenhauer

There is power in simplicity.

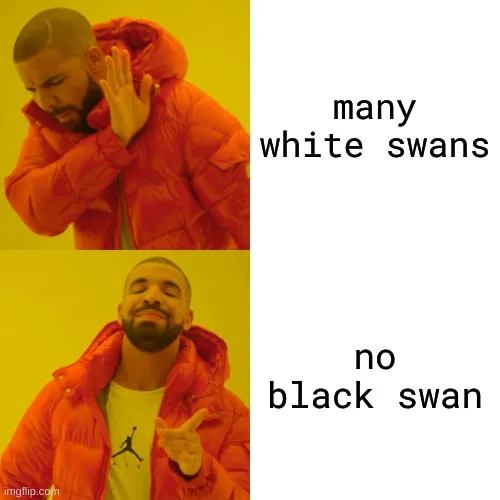

One example of simple ideas with extreme potential is Karl Popper's notion of falsifiability: don't try to prove your beliefs, try to disprove them. That simple principle solves important problems in epistemology, such as the problem of induction and the problem of demarcation. And you don't need to understand all the philosophy behind this notion, only that many white swans don't prove the proposition that all swans are white, but a single black swan does disprove it. So it's more profitable to look for black swans.

And we can use simple concepts to defend the power of simplicity.

We can use falsifiability to explain that many simple ideas being unconsequential doesn't prove the claim that all simple ideas are inconsequential, but a single consequential idea that is simple does disprove it.

Therefore I've proved that simple notions can be important.

Jump in the discussion.

No email address required.

Notes -

But we use those and more all the time. Pascal’s gambit and Schrodinger’s cat are almost too cliché for this venue. We have Pascal’s mugging, Moloch, a dane you can’t get rid of, a nazi who knocks, a cathedral, russell’s teapot, theseus’s ship, falsification, steelmanning, nash equilibrium, hypoagency, p hacking, oneboxing, backpacker harvesting, utility monsters, specks of dust, beliefs paying rent, pareto optimums, spherical cows, and, last but not least, the motte.

People’s complaints about this place are usually the opposite: that we use too much jargon, that we are being deliberately obscure. Or they will say the specifically rationalist concepts are not original. Which has a degree of truth, but if the point is to write more concisely, we still need to use the original term for the concept, and nothing will have been gained by switching names.

More options

Context Copy link