WestphalianPeace

No bio...

User ID: 184

By the late spring of 1941, stocks of coal in Germany were virtually non-existent and output was well short of requirement. At a meeting of the Four Year Plan at the end of June, General Hanneken reported that the German Grossraum faced an overall coal deficit of roughly 40 million tons. This reflected both the lagging production of the pits and the ever-increasing demands of Ger man industry. As a result, the occupied territories were being supplied at a rate of only 60 per cent of requirement. Within Germany, the steel industry was having its coal consumption throttled by 15 per cent and there was the threat that this might soon be increased to 25 per cent. Even the producers of electricity and gas could no longer be exempt. Cutting the coal allocated to households was not an option, since to ensure the continuity of industrial supplies in the first half of 1941, inadequate preparations had been made for laying in the necessary household stocks for the coming winter

pg 497

Behold. The masterpiece of Nazi Economic Gleichschaltung. The Party will Coordinate the whole economy. Industry and Community will become one. And shortages will become a thing of the past. The stern hand of the Leader will ensure that economic inefficiency, which is only a result of profiteering and sloth, will disappear.

By 1941 there were already signs of mounting discontent due to the inadequate food supply. In Belgium and France, the official ration allocated to 'normal consumers' of as little as 1,300 calories per day, was an open invitation to resort to the black market. Daily allocations in Norway and the Czech Protectorate hovered around 1,600 calories

well that's fine i'll just intensify agricultural production with fertilizers. wait. what's that? The explosive industry needs the same inputs?

But French grain yields depended, as they did in Germany, on large quantities of nitrogen-based fertilizer, which could be supplied only at the expense of the production of explosives. And like German agriculture, the farms of Western Europe depended on huge herds of draught animals and on the daily labour of millions of farm workers. The removal of horses, manpower, fertilizer and animal feed that followed the outbreak of war set off a disastrous chain reaction in the delicate ecology of European peasant farming. By the summer of 1940, Germany was facing a Europe- wide agricultural crisis. Danish farmers began systematically to cull their swine herds and poultry flocks. Dutch yields steadily deteriorated in line with the fall in fertilizer supplies. Most dramatic of all was the situation in France, where the grain harvest in 1940 was less than half what it had been in 1938.

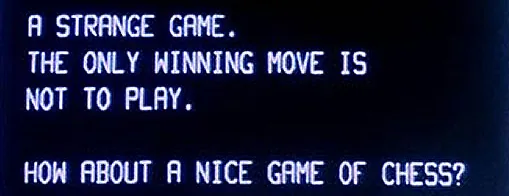

This is fine

The coal industry, however, had more immediate problems. Even though the German labour market authorities had seen to it that the mining industry suffered no net loss of workers at the start of the war, the Wehrmacht draft had taken the best young men. The result was a steady decline in per capita productivity. In due course, the industry could make up for this with further investment. But in the short term Pleiger needed emergency measures. As of the spring of 1941, Sunday shifts became a normal feature of life on the Ruhr, allowing the men not even a day to recover from their gruelling working week. To restore the quality of the workforce, the Wehrmacht was persuaded to return as many trained mine workers as possible to the mines. As the Wehrmacht office pointed out with remarkable frankness, this concession was necessary above all for political reasons.

when i play nation-state building games this is how I describe my ideal resource economy. First I rob my mines of labor for my armies. Then I make them work without rest. Then send the men I took from the mines to the armies back to the mines. Nothing says sound economics like the necessity of political reasons.

The disparity with respect to oil was most serious. Between 1940 and 1943 the mobility of Germany's army, navy and air force, not to mention its domestic economy, depended on annual imports of 1.5 million tons of oil, mainly from Romania. In addition, German synthetic fuel factories, at huge expense, produced a flow of petrol that rose from 4 million tons in 1940 to a maximum of 6.5 million tons in 1943. Seizing the fuel stocks of France as booty in no way resolved this fundamental dependency. In fact, the victories of 1940 had the reverse effect. They added a number of heavy oil consumers to Germany's own fuel deficit. From its annual fuel flow of at most 8 million tons, Germany now had to supply not only its own needs, but those of the rest of Western Europe as well. Before the war, the French economy had consumed at least 5.4 million tons per annum, at a per capita rate 60 per cent higher than Germany's. The effect of the German occupation was to throw France back into an era before motorization. From the summer of 1940 France was reduced to a mere 8 per cent of its pre-war supply of petrol. In an economy adjusted to a high level of oil consumption the effects were dramatic. To give just one example, thousands of litres of milk went to waste in the French countryside every day, because no petrol was available to ensure regular collections. Of more immediate concern to the military planners in Berlin were the Italian armed forces, which depended entirely on fuel diverted from Germany and Romania. By February 1941, the Italian navy was threatening to halt its operations in the Mediterranean altogether unless Germany supplied at least 250,000 tons of fuel.

pg 411

In my ideal economy we use the full economic potential of the countries we conquer by reducing their petrol consumption by 92%. Also I have to provide my allies with the fuel they need. Also I'm a net oil importer.

By the late 1930s, virtually every family in Germany held at least one 'savings book' (Sparbuch). The accounts of the Sparkassen thus provide a direct insight into the everyday financial dispositions of German households. In the months immediately preced- ing the war, they showed an unusually large net withdrawal, as millions of families did their best to stockpile necessities. Then, from the first months of 1940 onwards, as rationing began to bite and the shelves of the German shops emptied, the accounts of the savings banks swelled with a completely unprecedented volume of deposits. By 1941, the inflow was running at the rate of more than a billion Reichsmarks per month. Under normal circumstances, these funds would have been put to work as loans to local government, or mortgages for small businesses.

But wartime restrictions not only hit civilian consumption, they also bottled up civilian investment. Whilst construction of new armaments capacity accelerated after September 1939, investment in housing was cut to the bone. In 1937, the peak year for civilian construction in the Third Reich, a total of 320,057 apartments were added to the housing stock. By 1939, annual net additions had already fallen to just over 206,000, under the pressure of military construction demands. The year 1940 saw only 105,458 apartments added to the housing stock and by 1942 the annual total came to less than 40,000, a reduction relative to 1937 of 85 per cent."

In 1940 the Sparkassen alone channelled 8 billion Reichsmarks into the war effort. In 1941 they contributed 12.8 billion Reichsmarks. Private investors who held their funds beyond the Reichsbank's immediate reach were directed into government debt through the simple expedient of restricting the issue of any other forms of interest-bearing asset and putting a tight cap on stock exchange speculation. No compulsion was necessary. There was simply nothing other than government debt to invest in.

I'm told that the best possible economy is one where you literally can't do anything with your money except invest in Government debt. It's a good thing the government is propping up my wages. And also propping up prices. But the prices are hidden. But the wages are hidden. But also I can't change jobs.

The rail administrators struggled to ease the problems of freight traffic by cutting passenger services wholesale. But even drastic measures could not prevent a crisis. By early 1940, tens of thousands of freight cars were frozen in kilometres of traffic jams. By January, turn-around times had risen to more than a week. The effective carrying capacity of the Reichsbahn's rolling stock plummeted and the immediate result was an interruption to coal supplies. By December, the mines were warning of an impending 'transportation calamity'. In the freezing city of Berlin, coal ran so short that even a leading armaments firm such as Rheinmetall could not protect its deliveries from requisitioning by the desperate municipal authorities. Meanwhile, at the pitheads in the Ruhr, the mountains of undelivered coal reached dangerous levels, forcing the mines to slow down production. In total, in the early months of 1940 almost 10 per cent of German armaments plants were affected by the coal shortages. In the central industrial district around Kassel the figure was as high as 27 per cent. In January 1940 Goering described transport as the problem of the German war economy.

pg343-344

My ideal economy is one where lack of capacity of steel production results in a failing transport network where i have to cut off passenger service and yet still have a shortage of coal. In Germany.

The frustrations of the housing shortage were no doubt acute. But, more worrying for the Reich authorities was the impact of underinvestment on the German railway system. By 1938 the Reichsbahn was increasingly unable to cope with the combined demands of the Wehrmacht and a booming economy. Rail investment had been badly squeezed by the steel shortage. In 1938 the Reichsbahn was not able to obtain even half the steel it needed to maintain its current rail infrastructure and rolling stock. From the summer onwards severe delays affected the entire system. Huge pressure was exerted on freight workers to speed up loading and unloading. But by the last days of September, as the Munich crisis reached its climax, the Reichsbahn was nearing the point of collapse. Less than half the requests for freight cars were being met on time. There was no option but to go over to an overt system of rationing in which priority was given first of all to the Wehrmacht and then perishable foods, coal, sugar beet and high-priority export orders.

Help. My rail industry is getting 50% of the steel it needs and I need to ration who gets transport. Should I start a Great Power conflict against all of my neighbors?

And with the armaments effort reaching new heights, Goering's Decree for Securing Labour for Tasks of Special State Importance (Verordnung zur Sicherstellung des Kraeftebe- darfs fuer Aufgaben von besonderer staatspolitischer Bedeutung) of 22 June 1938 provided the Reich with general powers of conscription. Workers could be redeployed for any period required by the Reich, whilst their former employers were required to keep them on their rolls. By the end of 1939, no less than 1.3 million workers had been subject to such compulsory work orders. Though compulsion was not the norm in relation to German workers, any more than it was in the regime's dealings with German business, the possibility was now established that if rearmament demanded, the state could intervene in the working life of every single individual. In this respect as well, Hitler's regime clearly crossed a bridge in the summer of 1938. Perhaps not surprisingly, however, the rationing of labour functioned even less smoothly than the rationing of steel. The decree debarring rural workers from taking industrial jobs had to be abandoned, since, to avoid their children falling under the terms of the decree, rural families had taken to preventing them from entering farm work in the first place.

Meanwhile, in the inflation hot spots of urban Germany, the attempt to repress the market mechanism had only limited success. It was, after all, in the interests of neither employers nor workers to abide by the official wage restrictions. Workers wanted better wages and employers - keen to take advantage of the boom - were willing to pay for their labour. Given the formal ban on wage increases, the resulting upward adjustment of earnings was a covert process, hidden in accelerated promotion, high-status apprenticeships, retraining schemes, hiring bonuses, improved working conditions and a variety of supplementary social benefits. The extent of this 'wage creep' depended on the degree to which employers were subject to direct official oversight.

wages of destruction, pg 261

Nothing says "i'm developing an efficient economy" like compulsory work orders, forcing employers to keep workers on the rolls, and wage controls. Oh an forbidding rural people from taking industrial jobs. Good instincts there. Shame that second order effects exist. Who could have possibly imagined.

Some skilled construction workers were rumoured to earn better wages than senior army officers. And this was no accident. In May 1938, Hitler had removed control of the Westwall from the army's engineering depart- ment and handed it to Fritz Todt, the man idolized as the master-builder of the autobahns. Todt's mission was to complete the fortifications before the outbreak of hostilities and he was to do so regardless of cost. Goering's decree on labour conscription provided Todt with all necessary legal powers to secure the quarter of a million workers he needed. But typically for the situation of the German economy in the late 1930s he chose to supplement conscription with monetary incentives. The contractors on the Westwall were freed from standard military procurement rules, allowing them to inflate both their profits and their wage bills. By the summer of 1939, Todt had completed his mission. The most vulnerable sections of Germany's western frontier were reinforced with thousands of bunkers and gun emplacements. The price, however, was a huge inflationary shock to the labour market.

wages of destruction, pg 265

wanting to eat their cake and have it to. I want all my workers to have high wages. and i want the Westwall made quickly. but don't make it inflationary. and don't make it so that the high wage low-skill labour competes with agriculture.

From this point of view the fundamental explanation for the poverty of German agriculture was simple: low labour productivity. According to conventional measures, the productivity of the more than 9 million people employed on Germany's farms was roughly half that of the typical non-agricultural worker.84 What was really scarce in the countryside was not labour but the necessary capital and technology to use labour efficiently. Such productivity comparisons of course depended on the relative prices paid for agricultural and industrial products. And the RNS demanded higher farm prices, but this ignored the enormous gulf between the prices paid by German consumers for their food and the prices prevailing on world markets.85 By the late 1930s, however, the 'world market' as far as Germany was concerned was an increasingly irrelevant abstraction. Given the politicization of its foreign trade, Germany no longer purchased at 'world' prices. Instead, agricultural imports were bargaining items in a complex web of bilateral deals, in which Germany often paid substantial premiums for the willingness of its trading partners to remain loyal to the Third Reich.

wages of destruction, pg 266

a healthy economy is probably not one that has detached price signaling in exchange for political loyalty.

As serious as the situation appeared to be in agriculture, it was not the issue of milkmaids and dairy prices that really troubled Hitler's regime in the summer of 1938. After months of bitter argument, the problem of dairy farming was given a political 'fix' by raising the farm-price of milk by 2 Pfennigs. Since Rudolf Hess had made clear that an increase in the prices paid by consumers was out of the question, the conflict was resolved at the expense of the dairies, by squeezing their profit margins. This did not curb demand for milk. Nor was it enough to resolve the income deficit of German dairy farmers. But it did at least send a political signal that the regime was not oblivious to the interests of its agrarian constituency

wages of destruction, pg 268

a perfectly healthy economy. Months of political argument followed by the state setting prices and then demanding that those costs be born by the producer. Then being surprised when the demand for milk is the same.

I don't know the full extent of your knowledge of WW2. We could spend all day speaking past each other. You've got military production figures on hand from an archived source. I do take that seriously as more than the average person.

If you are interested, if you think the case is at least intriguing then please, at least watch the youtube videos. If you're convinced afterwards that I'm not arguing in bad faith then consider the books. Citino's books are actually rapt reading. Tooze is dry as a bone but if you can get past the first bit about manipulation of exchange rates then it becomes more engaging. The exchange rates chapters really do suck. It's worth it to get past them. I listened to it on audible and digested it over the course of a month. Because you get eye popping accounts of daily economic life like the following. Bolding & titles added by me

On the inability to stop a housing crisis in peacetime.

"Facing a continuing problem of overcrowding in the cities, in 1935 the Reich Labour Ministry launched an alternative vision of National Socialist housing in the form of so-called Volkswohnungen. Stripped of any conception of settlement or any wider ambition of connecting the German population to the soil, the Volkswohnungen were to provide no-frills urban housing for the working class, built according to the first projections for as little as 3,000-3,500 Reichsmarks. Hot running water, central heating and a proper bathroom were all ruled out as excessively expensive. Electricity was to be provided but only for lighting. Each housing unit was to be subsidized by Reich loans of a maximum of 1,300 Reichsmarks. Rent was to be set at a level which did not exceed 20 per cent of the incomes of those at the bottom of the blue-collar hierarchy, or between 25 and 28 Reichsmarks per month.

To achieve this low cost, however, the Volkswohnungen were to be no larger than 34 to 42 square metres. Though this was practical it was far from satisfying the propagandists of Volksgemeinschaft. The Goebbels Ministry refused to accept that accommodation of such a poor standard deserved the epithet 'Volkswohnung' and the DAF insisted that the minimal dimensions for a working-class apartment should be 50 to 70 square metres, sufficient to allow a family to be accommodated in three or four rooms.

But, as experience showed, the Labour Ministry's costings were in fact grossly over-optimistic. By 1939 the permissible cost of construction even for small Volkswohnungen had had to be raised to 6,000 Reichsmarks, driving rents to 60 Reichsmarks per month and thus pricing even this basic accommodation out of the popular rental market. The very most that working-class families were willing to pay was 35 Reichsmarks per month. Instead of the 300,000 per year that the Labour Ministry had intended, construction on only 117,000 Volkswohnungen was started between 1935 and 1939. As in the case of the Volkswagen, what Hitler's regime could not resolve was the contradiction between its aspirations for the German standard of living and the actual purchasing power of the population. But as in the case of the Volkswagen this did not prevent the D AF from espousing a Utopian programme of future construction.

By the late 1930s, the official ideal of 'people's housing' was a large family apartment of at least 74 square metres, fully electrified, with three bedrooms, one each for parents, male and female children. At the same time it was estimated that an apartment built to the DAF specification would cost in the order of 14,000 Reichsmarks, 40 per cent more even than those constructed by the Weimar Republic. The limitations of German family budgets, however, demanded that these generous apartments were to be provided to the Volksgenossen at monthly rents of no more than 30 Reichsmarks. In part, the costs would simply have to be borne by the Reich." - Wages of Destruction, pg 161

On the inability to produce cars economically in peacetime

In July 1936, the project began to slip definitively out of the hands of German industry. After a successful demonstration on the Obersalzberg on 11 July 1936 Hitler decided that Porsche's car was to be built, not in any of the existing car factories in Germany, but in a new special-purpose plant. Hitler claimed that this could be constructed for 80-90 million Reichsmarks. The factory was to have a capacity of 300,000 cars per annum and deliveries were to begin in time for the International Motor Show in early 1938. Faced with the impossibility of meeting the 1,000 Reichsmarks target on commercial terms, it seems that Germany's private car industry was on the whole content to see Porsche and his troublesome project transferred to the state sector. As a commercial project the VW was not viable. A factory built through the compulsory conscription of private business, along Brabag lines, would damage the entire industry. Far better to use public funds, or rather the funds of the German Labour Front (DAF). This suggestion seems to have come from Franz Joseph Popp, the founder of BMW, who also sat on the supervisory board at Daimler-Benz. Popp suggested that the DAF should take on the Volkswagen as a not-for-profit project. Non-profit status would qualify the factory for tax concessions that would help to cut the final price of the car. More importantly, from the point of view of industry, it would allow the sale of Volkswagens to be limited exclusively to the blue-collar membership of the DAF, thus reserving the profitable middle-class car market for the private manufacturers. The leadership of the DAF jumped at the chance. As Robert Ley, the leader of the DAF, later put it, the party in 1937 took over where private industry on account of its 'short sightedness, malevolence, profiteering and stupidity' had 'completely failed'.

In May 1937, with payments to Porsche and his design team totalling 1.8 million Reichs- marks, the industry cut its losses and ended its association with the VW project. On 28 May 1937 Porsche and his associates founded the Gesellschaft zur Vorbereitung des Deutschen Volkswagens mbH (Gezuvor). A year later, construction began on Porsche's factory at Fallersleben in central Germany. In October 1938, along with Fritz Todt and the aircraft designers Willy Messerschmitt and Ernst Heinkel, Porsche was awarded Hitler's alternative to the Nobel Prize, the German National Prize. The basic question, however, remained unsolved. How could the Volkswagen be produced at a price affordable to the majority of Germans? The DAF claimed that the Volkswagen was now to be promoted in conformity with Nazi ideology as a tool of social policy rather than profit. However, it too lacked any coherent system for financing the project. From the outset it was clear that the capital costs of building the plant would never be paid off by the sale of cars priced at 990 Reichsmarks per vehicle. The construction of the plant would therefore have to be financed through other than commercial means. The DAF, which had inherited the substantial business operations of Germany's trade unions, had assets in 1937 estimated to be as much as 500 million Reichsmarks. It also commanded a huge annual flow of contributions from its 20 million members. However, the demands of constructing the VW plant were enormous. Rather than the 80-90 million Reichsmarks originally mooted by Hitler, Porsche's planning now envisioned the construction of the largest motor vehicle factory in the world. The first phase, to reach a capacity of 450,000 cars per annum, was costed at 2.00 million Reichsmarks. In its third and final phase the plant was to reach an annual output of 1.5 million cars, enough to out-produce even Henry Ford's River Rouge facility. Investment on this scale placed huge demands on the DAF. The initial tranche of 50 million Reichsmarks to start work on the factory could only be raised by a fire sale of office buildings and other trade union assets seized after May Day 1933. Another 100 million were raised by over-committing the funds of the DAF's house bank and the DAF's insurance society.

The cars themselves were to be paid for by the so-called 'VW saving scheme'. Rather than providing its customers with loans to purchase their cars, the DAF conscripted the savings of future Volkswagen owners. To purchase a Volkswagen, customers were required to make a weekly deposit of at least 5 Reichsmarks into a DAF account on which they received no interest. Once the account balance had reached 750 Reichs- marks, the customer was entitled to delivery of a VW. The DAF mean- while achieved an interest saving of 130 Reichsmarks per car. In addition, purchasers of the VW were required to take out a two-year insurance contract priced at 200 Reichsmarks. The VW savings contract was non-transferable, except in case of death, and withdrawal from the contract normally meant the forfeit of the entire sum deposited. Remarkably, 270,000 people signed up to these contracts by the end of 1939 and by the end of the war the number of VW-savers had risen to 340,000. In total, the DAF netted 275 million Reichsmarks in deposits. But not a single Volkswagen was ever delivered to a civilian customer in the Third Reich. After 1939, the entire output was reserved for official uses of various kinds. Most of Porsche's half-finished factory was turned over to military production. The 275 million Reichsmarks deposited by the VW savers were lost in the post-war inflation. After a long legal battle, VW's first customers received partial compensation only in the 1960s. But even if the war had not intervened, developments up to 1939 made clear that the entire conception of the 'people's car' was a disastrous flop. To come even remotely close to achieving the fabled target of 990 Reichsmarks per car, the enormous VW plant had to produce vehicles at the rate of at least 450,000 per annum. This, how- ever, was more than twice the entire current output of the German car industry and was vastly in excess of all the customers under contract by the end of 1939. Assuming a production of 'only' 250,000 vehicles per annum - which was significantly more than the German market could bear - the average cost per car was in excess of 2,000 Reichsmarks, resulting in a loss of more than 1,000 Reichsmarks per car at the official price. Furthermore, even priced at 990 Reichsmarks the VW was out of reach of the vast majority of Germans. A survey of the 300,000 people saving towards a VW in 1942 revealed that on average VW savers had an annual income of c. 4,000 Reichsmarks, placing them comfortably in the top tier of the German income distribution. Blue-collar workers, the true target of Volksgemeinschaft rhetoric, accounted for no more than 5 per cent of VW's prospective customers. - Wages of Destruction, pg 156

I am not making my argument in bad faith. I stopped, considered your question and considered it legitimate. I tried to figure out which books would be best for an interested reader. I found talks the authors gave on youtube to summarize their arguments in case you didn't want to read Tooze's dry tome of a book. The book is ~800 pages long. It is dry. The talk is an hour & a 45. Believing that mere economics does not determine wars I recommend the most accessible operational history of the Germans to explain how they have a culture of achieving military victory inspite of poverty. I then remembered an illustrative case and provided a timestamped link to take you straight there.

You respond in 20 minutes, accuse me of bad faith, and provide as counter example a table of raw military production figures without consideration of any other economic factors.

I cannot help someone who, when provided extensive resources handmade specifically to make things easy, cannot even be bothered to look.

To anyone onlookers who've gotten this far. At least watch the Tooze video. See if my position is distortionary for yourself.

That's a very reasonable question! The mainstream account focuses on the dangerous potential and near victory of the Nazi's. It also tends of overlook economics in favour of operational accounts of the war. With a further focus on the sexy attention getting offensives of 1939-41 (42 for some).

For reading I would combine Adam Tooze's Wages of Destruction alongside Robert Citino's "Death of the Wehrmacht". The two compliment each other quite well. Death of the Wehrmacht deals with the military from the start up to 1942. His subsequent books The Wehrmacht Retreats for 1943 and The Wehrmacht's Last Stand are also engaging and accessible for average war nerd.

If you'd prefer the cliffnotes version here are some youtube video's for each.

Tooze economics highlight the constraints the domestic economy puts on the war effort. How resource & industrial capacity constraints affected decision making. Citino's account emphasizes continuity with the old Prussia tradition and the concept of Bewegungskrieg (Maneuver Warfare) over the incoherent concept of Blitzkrieg (a journalistic invention). Citino's account also explains why Prussia developed such a tradition, namely on account of the comparative poverty of Prussia and the awful geographic situation it was placed in. To quote from the first source online i could find that summarizes it neater than I can

Frederick the Great’s Prussia was a small resource poor kingdom, surrounded by more powerful states. To survive, its army’s military culture became one based on initiative at all costs. When a Prussian commander found the enemy, he attacked. The odds faced did not matter, while other forces converged on the battle. The goal was always a quick victory because Prussia could not survive a long war. As Citino highlights, taking a pre-industrial age concept of war and applying it to a 20th Century war of material worked as long as the enemy did not have time to draw upon their resources. Once the Soviet Union and the United States were in the war, Germany was up against the world’s titans of industry, but its Army’s concept of war was still mired in an age of lesser production. German commanders did not have any other plan nor was it possible for them to distil one. The blinders of culture ruled all decision-making.

I'd ask you to consider it this way: Germany starts off by fighting a bunch of small doomed states. Victory over Greece, Yugoslavia, Poland, Denmark, Belgium, & the Netherlands are not prestigious victories. They are assumptions. However the real impressive victory is over France and while this is an accomplishment it comes from a mix of French failure and German operational art. And it's an incredible upset that shocks the world!

But it does not come from a well calibrated economic engine developed by the Nazi's which overpowers the French in an attritional warfare contrasting each countries total industrial capacity. And the moment it becomes a match up between the other real players on the world stage, the UK, US, & USSR, the Nazi war economy simply isn't capable of handling the challenge.

also here's another great video by John Parshall of Shattered Sword fame comparing the Nazi tank production economics to that of the Soviet Union.

flipping back through it there is a great slide that really highlights things. From 43 minutes in:

On paper one the Henschel production facilities should be capable of producing 240-360 units. The highest monthly production goal was 95. The highest monthy production ever achieved is 104. For the majority of the lifespan of the Tiger they were averaging 60 tanks a month. 2 tanks a day.

I would suggest that having one of your major tank facilities only able to crank out 2 tanks a day while fighting the combined industrial might of the USSR, UK, & US might not be a sign that they had the best possible economic/industrial set up before the war.

so this is actually one of the really interesting parts of Wages of Destruction. It drives home the incredible degree to which Nazi Germany was this backwards economy pulling off a Potemkin village of industrialization. I'm recalling from memory but if i recall correctly

- an ongoing housing crisis sucking up peoples meager wages

- bizarre financialization schemes to trick people into buying vehicles they'd never get

- the inability to create a decent radio that could compete in the international market

- the average german still being so poor that their diet lacks sufficient protein

- lack of mechanization on farms

- large swaths of the economy still being literally small land owning peasant farmers

- subsequently an obsessions with land inheritance laws as early at 1933.

- price controls on both ends of the market for the purpose of political support.

- lack of enough labour for the farms requiring requisition/corvee labour/slavery

- still not enough food to create a net calorie balance

and finally not enough steel for everything. there's just not enough steel for construction, fortifications, tanks, airplanes, ships, & ammunition. Let alone the domestic economy. And so one of the central ideas in Wages of Destruction is that the Nazi state uses this scarcity of steel and turns it into a means of political control. Dolling out steel here and there to favour one industry/military faction over another.

The Nazi's take this total control and use it to focus everything into one area or another the result is visible, legible, & shocking. But it's going all out for short term sugar highs over and over again. And the underlying health of the economy is nowhere near that of the US, UK, or France. And it doesn't have the comparative scale of the capacity of the USSR.

There's also a few Hmong in French Guiana. Instead of bringing old allied Hmong to the metropole the French basically looked around, found an equivalent jungle geography, and sent them there. And instead of getting culture-bound diseases they flourished instead!

There's also several large enclaves of Mennonites/Anabaptists. I recall specifically in Bolivia and Argentina but there are probably some elsewhere.

Brazil used to have a sizeable Japanese diaspora in the millions.

My intuition is that it's

- an internal propaganda offensive to shore up internal support. Something to avoid the grinding stalemate narrative.

- a social taboo coup. US has restrictions on it's equipment being used to attack into Russian territory. Perhaps this offensive is intended to normalize the idea of fighting on Russia soil itself until the US gives permission to use donated equipment to strike inside Russia territory. There are many cases of Russia artillery attacking target in Ukraine and then scooting across the border to avoid retaliation. Get permission now and normalize the idea before the US presidential dice roll.

- There is no politics involved and it was just an intended to draw away Russian troops from further south. Russia has been slowly but successfully grinding forward there.

but mostly, be skeptical of anyone saying with certainty they know what it is.

Likewise for me.

I'd like to apologize to the critics of my post. Their comments deserve to be read as well.

It's a bad habit of mine to write in a fit of passion and then find myself unable to find the time or willpower to respond to critiques of my comments. But really, if you read my comment please also make time to read other people's criticism's of my case.

Should we bring back thee & thou?

We should.

As George Fox points out in his classic book titled

A Battle-Door For Teachers & Professors To Learn Singular & Plural; You to Many, and Thou to One: Singular One, Thou; Plural Many, You.

Wherein is shewed forth by Grammer, or Scripture Examples, how several Nations and People have made a distinction between Singular and Plural. And first, In the former part of this Book, Called The English Battle-Door, may be seen how several People have spoken Singular and Plural; As the Apharsathchites, the Tarpelites, the Apharsites, the Archevites, the Babylonians, the Susanchites, the Dehavites, the Elamites, the Temanites, the Naomites, the Shuites, the Buzites, the Moabites, the Hivites, the Edomites, the Philistines, Amalekites, the Sodomites, the Hittites, the Medianites, & c.

Also, In this Book is set forth Examples of the Singular and Plural, about Thou, and You, in several Languages, divided into distinct Battle-Doors, or Formes, or Examples; English, Latine, Italian, Greek, Hebrew, Caldee, Syriack, Arabick, Persiack, Ethiopick, Samaritan, Coptick, or Egyptick, Armenian, Saxon, Welch, Mence, Cornish, French, Spanish, Portugal, High-Dutch, Low-Dutch, Danish, Bohemian, Slavonian: And how Emperors and others have used the Singular word to One; and how the word You came from the Pope.

Likewise some Examples, in the Polonian, Lithvanian, Irish, and East-Indian, together with the Singular and Plural words, thou and you, in Sweedish, Turkish, Muscovian, and Curlandian, tongues.

In the latter part of this Book are contained severall bad unsavoury Words, gathered forth of certain School-Books, which have been taught Boyes in England, which is a Rod and a Whip to the School-Masters in England and elsewhere who teach such Books

We should value our language.

The problem with trying to make language rules explicit for students is that it violates two department's inclinations.

Linguistics majors are predisposed to fetishize change. They find language stability boring. Stability isn't why they got into this niche subject.

Meanwhile Education majors find education programs that work tremendously boring. They hate Direct Instruction, the 'Banking Model' of education, and they hate repetition. Doing sentence diagrams day after day isn't what inspired them to get into teaching.

What happens when you combine a group that finds teaching sentence structure boring with a group that thinks teaching kids grammar at all is inherently evil is that each group feeds into the other. The teachers are given an worldview that says they never need to teach sentence diagrams, they don't need to repeatedly explain the same concepts over and over again, and they don't have to awkwardly watch as some kids get it and some don't. The teachers in turn advocate for the linguist worldview. A Gordian knot is born.

One of the things Scott does not bring up is the lack of an easy narrative from the anti-woke right to allow people to an easy out. If you want victory over your opponents then make it narratively easy for people to recuse themselves until your opponent's coalition is miniscule. Give them plausible deniability, even if it's hollow. Make it as cheap as possible to defect from a coalition.

Your inspiration should be Winston Churchill fighting on behalf of Eastern Front legend General Erich Von Manstein to get him cleared of war crimes charges.

Within living memory of the war itself America & Europe constructed a narrative that recast Nazi's on the Eastern Front into Simple Soldiers merely Doing Their Duty, unaware of the war crimes amidst them. Even the former SS members were recast as what David Glantz describes "above reproach, knights engaged in a crusade to defend Western civilization against the barbaric hordes of Bolshevism". Which is bullshit of course, and to be clear Glantz arguing against this absurdity. But consider the power of the following narrative in giving people an out from their previous enmeshment with a regime.

The German army, or Wehrmacht, fought a "clean" and valiant war against the Soviet Union, devoid of ideology and atrocity. The German officer caste did not share Hitler's ideological precepts and blamed the SS and other Nazi paramilitary organizations for creating the war of racial enslavement and extermination that the conflict became.

The German Landser, or soldier, as far as conditions allowed, was generally paternal and kind to the Soviet citizens and uninterested in Soviet Jewry. That the German military lost this war was due in no way to its battlefield acumen, but to a combination of external factors, first and foremost Hitler's decisions. According to this myth, the defeat of Germany on the Eastern Front constituted a tragedy, not just for Germans, but for Western civilization.

For decades that narrative gave people an excuse. It took until the 90's for Germans to confront the reality of what the Wehrmacht did. But in that crucial period after the war there was a narrative path for millions of people to distance themselves from evil. Interested WW2 amateurs today decry the existence of wehraboo's and how many Japanese and West German officials were former members of their respective regimes but when I compare what happened with de-baathification it sure looks pretty efficacious.

and what's remarkable is that Scott directly links to Yarvin but only regarding Yarvin's coining of the term Brown Scare. And merely linking to Yarvin is a massive risk to Scott's reputability. But in spite of taking that risk he avoids the more relevant to the point at hand which is that Yarvin, from the ultra-right, makes a similar case for avoiding cycles of retaliation by means of giving people an out.

"There's a funny fact about regime change. The federal republic of Germany is still paying pensions not only to retired Stasi officers but also to retired Wehrmacht officers. It is accepted that both of those regimes were Germany. If you served those regimes, and you wern't some major criminal who was prosecuted, yeah, you're entitled to your pension. And the way that shut down worked is, that the day the doors of the stasi building were closed and these people were sent home, you couldn't reboot that system."

Yarvin is also fond of telling parables of Caesar constantly forgiving his enemies. He tells a tale of Caesar winning a battle and scavenging a bag full of letters that would allow his faction to engage in reprisals against every single person who supported his enemies. And that's Caesar's response was to burn the bag. A point independently echoed by Mike Duncan of the History of Rome podcast where Duncan points out that resolution of the civil war basically required someone to take it on the chin and not engage in property confiscation and tribunals after total victory.

So lets simplify and add one more bullet to Scott's list at the end of how to approach this problem instead of massive retaliation.

- Remove the laws that give rise to this culture

- Encourage universities to follow the Chicago Principles

- Improve internet moderation

- Make what Cancel Culture is explicit, not generable

- Weave a narrative that allows for mass defection

Sid Meir observed that people simply cannot process probabilities.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=MtzCLd93SyU&t=1168

"We found that there is this point, and it's kinda around 3 to 1, 4 to 1, where people do expect to pretty much win everytime"

30% doesn't mean about 1 in 3. It means impossible. He had to manipulate how the numbers played out in the background so that it fit with people's sense of what probabilities mean, rather than actual probabilities playing themselves out.

So far the only luck i've ever had explaining it to people is to say "most pollsters thought it was impossible. Silver said it was unlikely but about the same chance as hitting a baseball. and people do hit baseballs"

For some reason the baseball analogy is the only thing that seems to crack the innumeracy.

- the amount of calories in X doesn't count because 'it's good for you'.

- dividing 4 by 2 is too much math. calories counts are whatever it says in bold. checking serving amounts is an unreasonable and absurd ask

- "you can't expect me to just not socialize" when it's pointed that dieting and then a full meal at a restaurant twice a week is futile

- Prev

- Next

Ck3's gameplay loop is kinda immersion breaking once figured out. You start seeing the same events over and over.

Two solutions

Of cultural note relevant to this forum specifically. CK2's After the End mod actually had a bunch of rat references. Yudkowsky founds the empire of California, founds a religion whose focus is to emphasize different teachers but no singular authoritative source, and you start with the rare artifact "Meditations on Moloch"

The CK3 mod did away with all of this and I believe the cultural uniqueness of AtE is worse for it.

More options

Context Copy link